Scott Stokely Has Layers

Scott Stokely Has Layers

The former world number two on teaching disc golf, throwing far, and chasing Climo

Scott Stokely has been touring and teaching disc golf professionally since the early 1990s, seen here with student John Rubio at TC Jester Disc Golf Park, Houston, TX. Photo: Michelle Deering, Michellustrations Photo & Design.

Scott Stokely may be the greatest player to have never won a PDGA Professional Disc Golf World Championship.

During the mid-to-late 1990s, he produced a succession of top-five finishes, including consecutive second-place showings in 1997 and 1998 that established him as the clear world number two. Still, he never quite managed to wrest the sport’s ultimate prize from the iron grip of the man known simply as “The Champ.”

Stokely may also be the most important figure in the history of the sport who has yet to earn a place in the Disc Golf Hall of Fame. Beyond his accomplishments on the course — his top-five Worlds finishes, his multiple national pro doubles titles, his world distance records — Stokely made a lasting impact on the game through a number of pioneering efforts and innovations, many of which he has written about in his new memoir Growing Up Disc Golf. He was one of the first players to earn a living while on tour and one of the first to organize clinics around the country. His groundbreaking sponsorship deal with Discraft changed the way manufacturers approached player partnerships, and his prodigious power off both forehand and backhand wings inspired an entire generation of pros to incorporate sidearms into their game.

Never one to mince words, Stokely will be the first to tell you that he still thinks he’s the best in the world. It’s just that now it isn’t that he’s the best player, or the longest thrower; it’s that he’s the best teacher. If you think this sounds arrogant, it does. And Stokely agrees. “But,” he says, “you just can’t argue with the results.”

I recently had the opportunity to speak with Stokely as he took an unexpected break from his tour across the country teaching private lessons and promoting his book.

Scott, thank you so much for taking the time to speak with us. How are you holding up through all of the coronavirus madness?

Scott Stokely: Yeah, I’m doing pretty well. Just feeling a lot of empathy for all of the people who are going to be affected by the virus.

We’ve been seeing a lot of great responses to your private disc golf lessons. What do you think has made you such a popular teacher?

SS: I think it’s because everything I teach is very practical and everything is based on my experience helping people improve their games. It’s not based on theory. It’s about hundreds upon hundreds of people that, after I have them do thing “A” rather than thing “B,” thing A makes them throw better and thing B does not. It’s a systematic approach of making it work, of determining what works and then building on it.

I really don't think you can learn how to teach disc golf by breaking down YouTube videos. You’re not a teacher because you can get out a chart and look at a certain player’s form and how their hips are opening up. That’s not teaching how to throw a disc. That’s not even close.

What I do is build layers. I start with, "You’re going to do this step first. And then once you have this step, we’ll add this next step, and this next step" — and we add layer upon layer upon layer, and we stay at each step until the person gets that and they don’t have to think about it. So their mind is free to think about the next step. We add layer upon layer, and we do this until that person is able to throw correctly.

Signing discs for happy fans at a Blue Power Clinic. Photo: Blue Power Disc Golf

Is your approach to teaching the same when working with newer players as it is working with 1000-rated players?

SS: With 1000-rated players, it’s not about revolutionizing their game. They’re already great. It’s about finding things we can fine-tune. It might be just removing a variable from their throw that’s not necessary for the throw. You have to do things that can be replicated — that’s a critical part of all this. Every single thing that you do in your throw, you have to replicate every one of these every time or else your timing is going to be off. If your timing is off, your throw is off. The more things you have to replicate, the more things that you can get wrong, the more frequently your timing’s going to be off. So with these players it’s not about having the mechanics to throw far and to throw well — they have those. But there may be some things in their throw that are unnecessary to the throw that they are now having to replicate every single time. If we eliminate those things, then it’s one less variable they have to account for. Remove the variables, and the percentage of times that they’re going to throw correctly goes up.

Have you made any changes to your own throwing technique over the years?

SS: Absolutely. Unfortunately, my backhand finesse game was terrible when I was younger. My backhand finesse game now, at age 50 — playing significantly less than I played before — is night-and-day superior to what it was before.

A lot of things I figured out really early on, like not having a sidearm is crazy; hyzers are more mathematically probable to be successful than anhyzers, you can’t even compare the two. Not having a sidearm was always silly to me. That’s just logic. That’s just probabilities and creating a larger margin for error. There’s mathematical reasons why a sidearm hyzer will be more successful than an anhyzer, or will get to the target a higher percentage of the time just because the margin for error is so much larger. No one argues with me about this anymore, but they did argue with me about it in the 1990s.

Why do you think sidearms were so underutilized early on in the development of the sport?

SS: I think it’s just because the backhand is an easier throw to learn. The reason why a backhand is an easier throw is because the disc requires spin to fly, and the faster the disc flies the more spin it needs — so it’s not how much spin it has, it’s spin relative to speed. Every backhand in the history of backhands has had enough spin. That’s why, when you think about throwing a Frisbee, it’s a backhand throw. Two guys buy a Frisbee at the grocery store and they go out to the park — they can throw backhand. They can’t throw sidearm yet, because with sidearm you have to deliberately develop the skill of putting spin on the disc. So, spinning the sidearm enough is a learned skill that doesn’t come naturally. That’s why the “natural” way to throw a Frisbee is with a backhand. For some reason, players just didn’t develop the skill of throwing sidearm because their backhand was initially better and when they tried throwing sidearm, the sidearm wasn’t as good. And, they didn’t have anyone to show them the correct way to throw. That’s all it was — there was nobody showing them how to do it.

Right now, when you're new, you see right off the bat people are throwing sidearms, and so there's this initial commitment to that throw because it’s a recognized part of the game. There’s a critical mass when enough people are throwing sidearm that then new people throw sidearms also because they’ve seen it. That wasn’t the case in the 1990s, so new players then just saw backhands.

Did other pros in the 1990s try to adopt the sidearm throw after seeing how well it was working for you?

SS: Eventually, yes. There’s people like Mike Randolph and Steve Rico, and some other players that had a sidearm. But it was very situational, and it was never interchangeable [with their backhand]. However, people like Gregg Barsby and Nate Sexton came to my clinics in the 1990s when they were kids, so I reached that generation of players. I reached the next generation. I originally went to 155 cities doing throwing clinics, so I traveled around the country and reached a lot of people. And then my book and my DVDs [were released] showing everybody how to throw sidearm. People were throwing sidearm after that, you know? I had a lot to do with that, for sure.

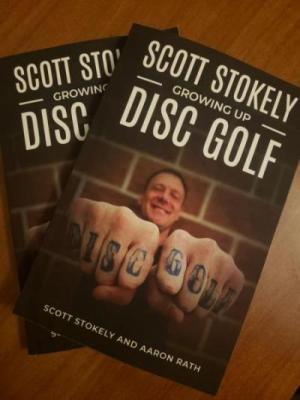

Scott Stokely's new memoir recounts stories from a disc golf career that has spanned more than four decades. Photo: Scott Stokely

Who did you learn from when you were coming up?

SS: A lot of people helped me. Joe Ursino helped me. Frank Aguilera, Scott Zimmerman, Rick Schafer, Mark Horn, Dan Roddick. A lot of people contributed to me being able to throw when I was younger, and then it evolved from there. When I got older I spent a lot of time with Chris Voight — we spent a lot of time analyzing distance [throwing]. Mike Randolph. Darrel Nodland. Jeff Malkin helped me out a bunch. I learned from everybody who was good.

The problem was that we just didn’t understand what worked in the 1990s yet. Right now we’re to the point where we understand the mechanics and that there’s a correct and an incorrect way to do most things. There are a lot of different styles of throwing, but when it comes down to it there’s very few different ways that the top players actually throw the disc. At the core level everyone throws very similar. Think about it like in tennis, where (Novak) Djokovic can do impressions of all the different pro players and everybody in the audience knows exactly which player he’s doing an impression of with their serve. But the mechanics of the serve are the same for everybody — or, at least, extremely close.

When you watch the top players, you’ll see what looks like a lot of different techniques. But they’re not really different techniques — they’re different styles. But most of the techniques are pretty similar, or at least the basic fundamentals have a lot in common. It wasn’t that way in the 1990s. It was a lot more all over the place, for sure.

Has the sport shifted too far toward the distance/power game?

SS: No. At the Memorial, for example, it’s only a big, long power game because you’re playing a course in Phoenix. That’s all there’s going to be out there, there are no woods. I always thought that throwing far and throwing accurate were two different skills. What happened a lot of times in the 1990s — when someone talked about making a course longer, or if I suggested that it would be great if courses were longer, people would say, “Well, that would be unfair because only you can reach the holes.” I always thought that was wrong because I had developed a skill that would allow me to get it. If other people hadn’t developed that skill to throw far, that’s not the course designer’s fault that other players lacked that skill. Instead, they built all these courses, generally speaking, where everybody could reach every hole. But players who weren’t as skilled at throwing accurately would be lacking a skill that would be an advantage to the finesse players. There’s no difference. But, no. I don’t think the courses are too long now — I think it’s great.

The finesse game still exists on every hole where there’s an approach shot. There are also lots of courses that are wooded and do have those challenges. And even wide-open courses with a lot of OB require finesse. If a shot is long but lined with OB on both sides, nobody is throwing a 600-foot shot.

Do you think your career would have played out differently if you had come up during the 2000s rather than the 1990s?

SS: Sure. My game in the 1990s was much more of a well-rounded game and was developed for a different time. I mean, it’s hard to say. The players I was playing against, I threw so much further than them that if the course was long it was a big advantage. I used to win Nationals every year in Austin because that was a 9,000-foot course, and I was always the favorite to win there. Yeah, I have wondered what it would be like if I could play in the modern era. I also wonder what it would be like — you know, I had a hard time with touch putting. I wasn’t the best putter back in the 1990s. I became a much better putter later on when I could actually be more aggressive. So even the touch putts that were required on Mach 3 baskets weren’t necessarily my strong suit back then.

Are players today still able to get an advantage by using variety in ways other players don’t?

SS: No. They’ve all got it, just about. Now you are simply at a disadvantage when you don’t have those shots. All you have to do is look at hole 17 at USDGC. If you’re right-handed, you should be able to throw that on to the green with a sidearm in your sleep. With a backhand it’s a missable throw; with a sidearm it’s really not. And we just saw twice in the last five years that hole turn into a disaster for somebody without a sidearm. You are now at a disadvantage if you don’t have a sidearm, but if you have a sidearm it’s routine.

I’ll make this prediction: In the same way that in the 1990s I said that everyone would need to have a sidearm someday, the future of disc golf throwing technique that is already implemented a little bit but nowhere near to the degree it will is that players will have two incredibly well-defined different backhand techniques. They’re going to have a control backhand and a power backhand. Right now, most players have a hybrid between the two. They have one way of throwing backhand, with a slight modification for throwing a finesse shot versus a power shot. But it’s going to become two different throws. There’s no reason why a young player isn’t out on Tuesdays and Thursdays throwing like Michael Johansen and out on Mondays and Wednesdays throwing like Simon Lizotte. That’s what players are going to have someday. No one is going to have a hybrid backhand in the next generation.

If you had a team of Michael Johansen and Simon Lizotte, and whenever you stepped up to the tee you got to decide which of them would throw — that’s a world champion. There’s no reason why players wouldn’t develop to different techniques. That will be the next generation, I promise.

Speaking of Simon, here’s a guy who throws lines that nobody else can throw, and who’s right at the top of the game without yet winning a world championship. Do you see parallels between him and yourself?

SS: Absolutely, 100 percent. The thing about Simon is, he’s not showing off for the crowd. He’s throwing the shots that he thinks will give him the best chance to succeed, and they don’t look like other players’ shots. Simon is not a finesse player, and when you’re not a finesse player there are lines that you should not be throwing. Just because everyone else is throwing a certain shot — they’re playing the percentages according to their game. For Simon, that’s not where his probabilities are. Simon also has to make up strokes in other places. In tournaments, he has to be throwing shots where he can get those bonus birdies because he’s not going out-tunnel shot you — he’s going to lose strokes there. So he’s got to make them up somewhere. He’s got to play to his strengths.

It was the same thing for me. I never threw over the trees because I was trying to impress the guys in my group — I threw over the trees because I couldn’t throw through them.

How much did you care about winning?

SS: I always want to win. I’ve never competed for second place. If I go to a tournament today and you ask me if I think I’m going to win, the answer is yes. If you ask me to seed myself, I might seed myself 43rd. But if you ask if I’m going to win, I would tell you, “Yes I am.” I always think I’m going to win. I don’t know how to approach anything in life other than that. I always expected to win. I always wanted to win.

You won a number of doubles world titles and were probably the best doubles player in the world during the '90s. What was it about your game and your approach to the game that made you so good at doubles?

SS: There’s really two things. One is that in doubles I could get a partner who could hide my weakness, which was my finesse game. If I had somebody on my team that could make the finesse shots, I could make everything else — the sidearm shots and the long shots. When you’re more of a one-dimensional player, doubles can hide those weaknesses. So, that’s one part of it.

The other part is that I never get upset when I’m playing. I don’t get upset. I don’t get angry. I don’t get stressed out. I just don’t exist in that space. I’m usually very level-headed and calm, and that will bring out the best in my teammate because that’s what you want in your teammate. It’ll simultaneously make it hard for your competition, because when you’re not flustered by anything then it can be a bit unnerving. It’s not really a head game, but when you’re calm and cool and collected and someone else is stressed out because it’s a big tournament, it makes you tougher to play against. That’s also the way I would play in singles, but in doubles that thing that made it difficult to play against me also made it easier to be my partner because I’m going to make jokes. If my partner throws a bad shot, I’m going to make fun of it. I’m going to laugh at him. And I’m going to make fun of my bad shots. The next thing you know we’re playing better because we’re having fun.

Was the 1994 National Doubles Championship playoff win your biggest win over Ken Climo?

SS: Most of my wins over Ken were in doubles. He pretty much owned singles. Ken pretty much beat everybody, all the time. That was kind of his job. But it wasn’t more significant because it was over him. It was my first national pairs title that I won in sudden death. I liked it because it was a 560-foot uphill hole that I rolled like 10 feet from the basket with a speed-six disc. So, yeah, that was pretty cool. It was a hole that had never been two’d in tournament play before.

You wrote that afterward Climo sort of threw up his hands and said, “We played perfect. That’s all you can do is play perfect.”

SS: That’s all you can do. They birdied every hole. His team and my team birdied every single hole, and then we eagled. So, that’s all you can do — if you birdie every hole and still lose. So, yeah.

What was it like to compete against Climo during his prime?

SS: He just played without mistakes. He would never miss a putt inside 20 feet. He rarely missed a putt within 30 feet. He rarely didn’t two a hole under 300 feet. It was just that he made all the shots you’re supposed to make — the ones that are routine, that a good player hits 90 percent of the time, he would hit 100 percent. It means that you had to play perfect to beat him. He just didn’t play bad. And that’s difficult, because when someone doesn’t have an off day — it kind of sucks (laughing). I don’t know what else to say. It’s hard to compete against.

But nowadays there are so many good players that there will always be a player having a good day at every tournament. So you’ll never go to a tournament where there aren’t a bunch of people having good days. Competing nowadays — there is so much depth, and the fields are so good. There are a few guys at the top that stand out a tiny bit, but it’s ridiculous how deep and how good the fields are.

Do you think it will be possible for someone to dominate the game again like Climo did in the 1990s?

SS: Yeah. I mean, Paul [McBeth]'s doing it. He’s not going to win the same percentage, but what Paul’s doing right now is just stupid. With as deep as the field is and the quality of play, for someone to win at the frequency he does is ridiculous. It’s not even right. There is a gap between Paul and everybody else — I don’t care if the ratings show that it’s 10 ratings points to the next best guy. The gap is bigger than that.

Scott Stokely’s new book, Growing Up Disc Golf, is available now on Amazon.com. Parental advisory warning: The book contains graphic language and adult themes. You can also check out his latest instructional article in the Winter 2020 edition of DiscGolfer Magazine.

- posted 1 day ago

- posted 1 week ago

- posted 1 week ago

- posted 2 weeks ago

- posted 3 weeks ago

- 1 of 700

- next ›

- posted 6 days ago

- posted 4 years ago

- posted 6 years ago

Comments

That's a great interview with

That's a great interview with Mr. Stokely. Learned a lot.

His lessons are a lot like learning martial arts.

Layered.